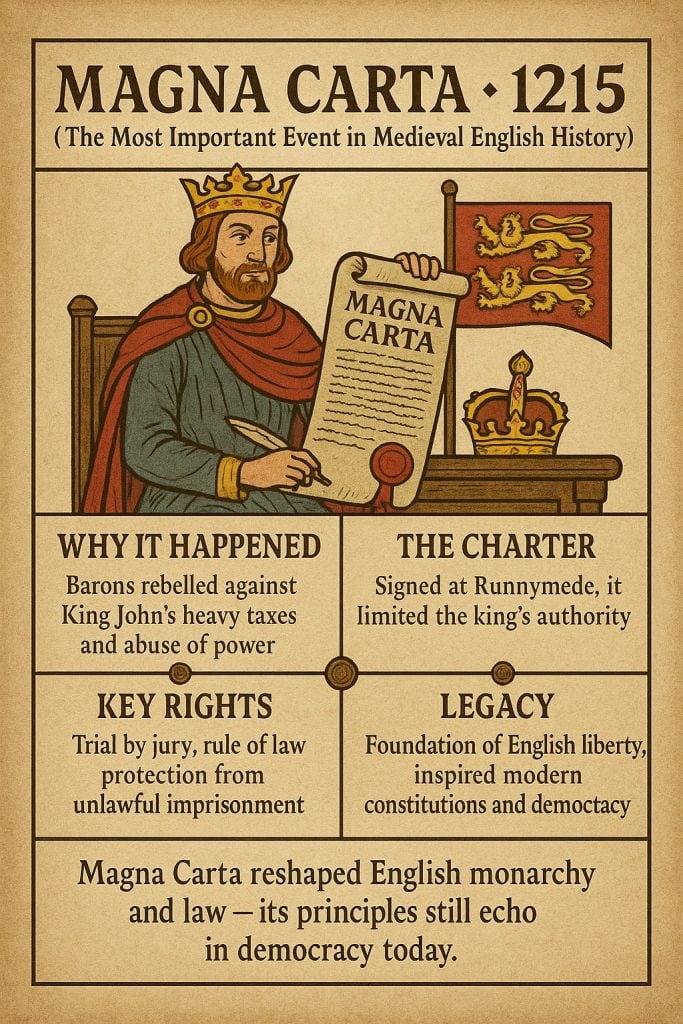

In 1215, at a riverside meadow called Runnymede, one of the most important documents in medieval and world history was sealed: the Magna Carta, or “Great Charter.” Originally created to resolve a bitter conflict between King John of England and his rebellious barons, the charter soon became much more than a political peace treaty. Over the centuries, it evolved into a powerful symbol of liberty, lawful government, limits on royal power, and the fundamental idea that even the king must obey the law.

Though its medieval origins were specific to English barons and feudal grievances, the Magna Carta ultimately influenced the U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and even the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Its legacy is far larger than the world of feudal England that produced it.

Why the Magna Carta Was Created

King John’s heavy taxation, military failures, and arbitrary justice angered the English barons, pushing them to rebel and demand written limits on royal authority.

Runnymede: The Historic Meeting

In June 1215, King John met the rebel barons at Runnymede, where negotiations produced the Magna Carta—the first formal document placing constraints on an English monarch.

Key Principles Introduced

The charter affirmed that the king was not above the law, protected rights to fair justice, and prevented unlawful imprisonment—foundations for later due-process traditions.

The Famous Clause on Liberty

Clause 39 declared that no free man could be imprisoned or punished without “lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land,” a precursor to modern legal rights.

Why the 1215 Charter Failed

King John sought annulment from Pope Innocent III almost immediately, sparking renewed civil war—yet later kings reissued revised versions to secure political support.

Long-Term Global Influence

Over centuries, the Magna Carta inspired constitutional developments in England, the United States, and beyond, shaping ideas of human rights, limited government, and the rule of law.

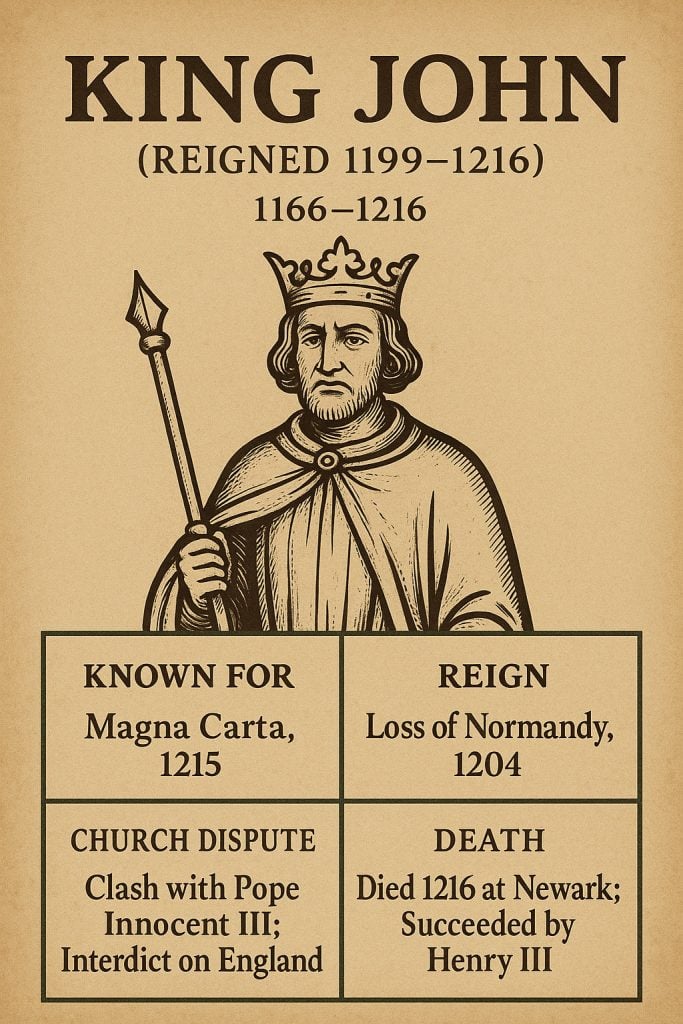

Causes of the Crisis: Why the Barons Rebelled

By 1215, King John had become one of the most unpopular rulers in English history. His failures included:

- Heavy taxation to fund failed wars in France

- Harsh legal punishments and arbitrary justice

- Loss of Normandy and other key territories

- Conflict with the Church, including his excommunication

- Seizure of baronial lands for political gain

The Northern Barons, who suffered the most from John’s taxation and bullying, rose in open rebellion. To prevent civil war, Archbishop Stephen Langton, acting as mediator, arranged negotiations between the two sides.

The meeting place: Runnymede, between Windsor and Staines.

💡 Did You Know? — Causes of the Crisis: Why the Barons Rebelled

The barons’ rebellion against King John wasn’t just about taxes—though heavy and repeated taxation played a major role. Their anger grew from a combination of military failures in France, abuses of royal justice, and the king’s habit of demanding payments far beyond traditional feudal expectations. Many barons believed John was ruling arbitrarily, ignoring established customs and exploiting his authority for profit.

By 1215, their grievances had reached breaking point. The crisis at Runnymede was the culmination of years of mistrust, financial strain, and a widespread belief that the king himself was violating the very laws and traditions he was meant to uphold.

The Sealing of the Magna Carta – June 1215

On 15 June 1215, King John affixed his seal to the Magna Carta, and it was formally confirmed four days later on 19 June.

Most of the terms had already been negotiated beforehand. Key promises included:

- No taxation without “common counsel”

- Fair and lawful trials

- Protection of baronial rights

- Limits on feudal abuses

- Restrictions on arbitrary imprisonment

These principles may sound modern, but this was the first time in English history that a king was forced to accept written limitations on his power.

King John Breaks His Oath

Despite sealing the charter, John never intended to honor it. Within months, he appealed to Pope Innocent III, who declared the Magna Carta invalid.

War erupted again between the king and the barons.

Desperate, the rebels invited Prince Louis of France, son of the French king, to claim the English throne. Louis accepted and crossed into England with an army.

Before the conflict could be decided, King John died suddenly in October 1216, leaving the throne to his nine-year-old son, Henry III.

A Child King and a New Beginning

With John gone, many barons switched sides. A foreign king on England’s throne now seemed less appealing.

They crowned Henry III, only nine years old, knowing that a child ruler meant they would effectively govern the kingdom. Prince Louis, seeing the political tide turn, withdrew and abandoned his claim.

To stabilize England, Henry’s guardians reissued the Magna Carta in a revised form in 1216 and again in 1217 — this time as a genuine foundation for peaceful government.

Henry III’s Rule and the Return of Barons’ Power

As Henry grew older, he began exercising full authority. But his:

- lavish spending,

- favoritism toward foreign relatives, and

- marriage to Eleanor of Provence,

angered many nobles.

Though the Magna Carta had been reissued several times, Henry often ignored its principles, ruling without consultation when it suited him.

This led England toward another constitutional crisis.

🏰 Henry III’s Rule and the Return of Barons’ Power

After the turbulent reign of King John, his son Henry III inherited a kingdom still shaped by the demands of the Magna Carta. Although Henry initially reaffirmed the charter to secure stability and support, tensions resurfaced as he frequently relied on foreign advisers, mismanaged royal finances, and pursued ambitious building and crusading projects that strained the treasury.

These pressures revived baronial influence. Led by figures such as Simon de Montfort, the nobles pushed for greater accountability, insisting that royal decisions—especially concerning taxation—require baronial consent. Their efforts culminated in the Provisions of Oxford (1258), a landmark attempt to limit royal authority and broaden political participation.

Under Henry III, the issue that began at Runnymede resurfaced: where should the balance of power truly lie—between the crown and the realm’s leading nobles?

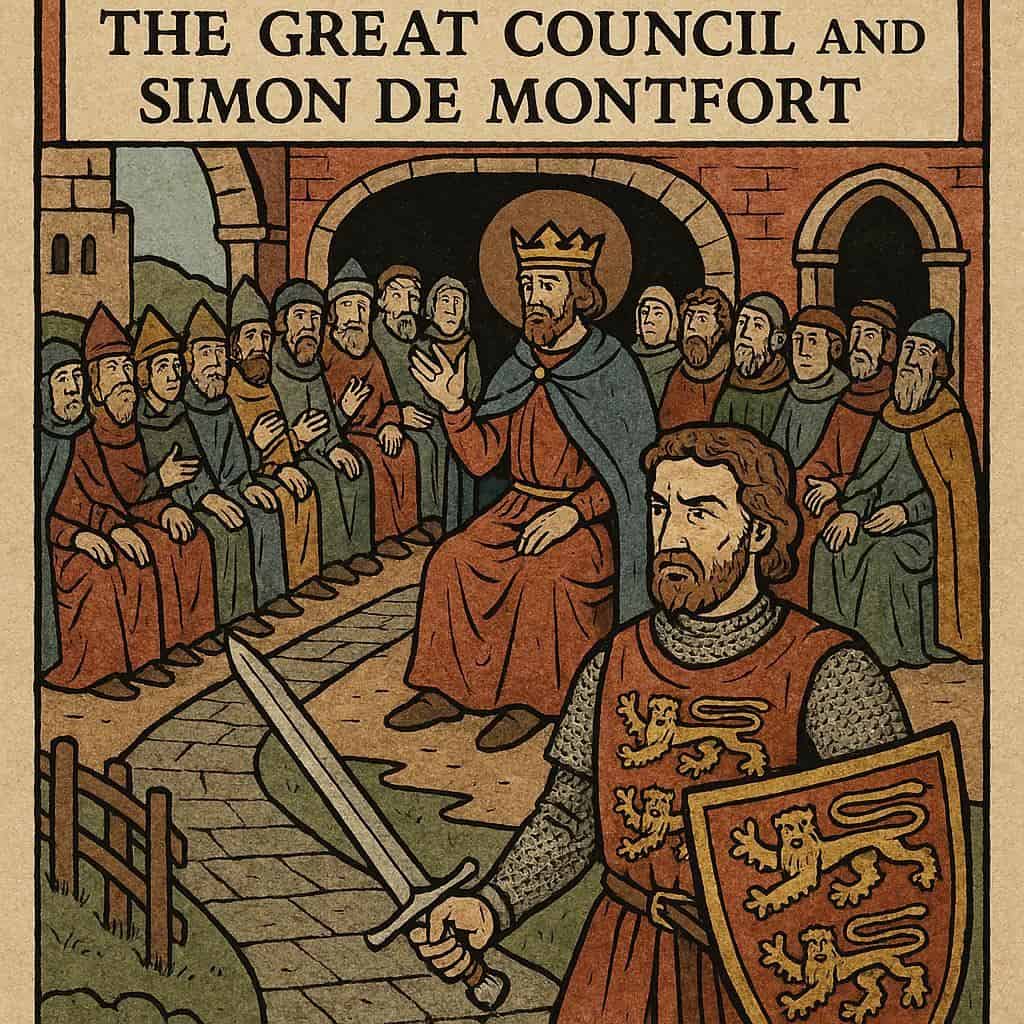

The Road to Rebellion: The Great Council and Simon de Montfort

By the late 1250s, the discontented barons forced Henry to accept the Provisions of Oxford, which required that he rule with the approval of a council — the beginnings of a parliamentary system.

Henry soon renounced the agreement, sparking the Second Barons’ War.

Under Simon de Montfort, the king’s brother-in-law, baronial forces defeated Henry at the Battle of Lewes (1264). For the first time in English history, a king was captured and held prisoner.

As de facto ruler, Simon called a revolutionary assembly in 1265, including:

- barons

- knights

- townsmen

This gathering is widely regarded as the first true English Parliament.

The Rise of Edward – and the Fall of Simon de Montfort

Henry’s son, the future King Edward I, escaped captivity and rallied royalist forces in Wales.

At the Battle of Evesham (1265), Edward crushed the baronial army. Simon de Montfort was killed, and Henry III was restored to power.

Although the rebellion was defeated, the idea of a broader representative council — and the principle that kings must consult the realm — survived.

Edward I: The King Who Strengthened the Magna Carta

When Edward I succeeded his father in 1272, he took a more constructive approach.

He:

- confirmed the Magna Carta multiple times,

- expanded the Great Council,

- invited knights and townsmen regularly,

- laid the foundations for a permanent Parliament.

Under Edward, the Magna Carta became more than a barons’ document — it became central to English law and medieval government.

⚡ Fast Facts: Magna Carta at a Glance

- Year introduced: 1215

- King: John, son of Henry II (not Richard III)

- Why it happened: oppressive taxes, failed wars, and royal abuses

- Immediate effect: ended civil war temporarily

- Long-term effect: foundation of constitutional government

- Henry III & Edward I: reissued and strengthened the charter

- Legacy: basis for English Parliament and later democratic principles

- “Parliament” comes from: French parler, meaning “to speak”

The Magna Carta is often called the first step toward democracy in England.

The Lasting Legacy of the Magna Carta

Although only a handful of its original clauses remain in modern English law, the spirit of the Magna Carta endures. Its central message — that no one is above the law, not even the king — reshaped medieval England and continues to influence legal systems around the world today.

It inspired:

- the Petition of Right (1628)

- the English Bill of Rights (1689)

- the U.S. Constitution & Bill of Rights (1787–1791)

- global human rights movements

What began as a peace treaty between an unpopular king and angry barons became one of the cornerstones of modern liberty.

📜 Key Takeaways: The Magna Carta

- The Magna Carta was signed in 1215 by King John under pressure from rebelling English barons.

- It is one of the most influential documents in Western political history, limiting royal power and protecting baronial rights.

- The charter established the principle that the king was not above the law, challenging centuries of unchecked monarchal authority.

- It introduced early ideas of due process, such as protection against unlawful imprisonment — the foundation of habeas corpus.

- The Magna Carta originally failed and was annulled shortly after its signing, leading to the First Barons’ War.

- Later reissues of the charter, especially in 1225, helped secure its place as a cornerstone of English constitutional tradition.

- Its legacy inspired later democratic movements, including the English Bill of Rights, the U.S. Constitution, and global human rights law.

- Today, only a few clauses remain in English law, but its symbolic significance as a guarantee of liberty endures worldwide.

❓ Magna Carta (1215) – Frequently Asked Questions

What was the Magna Carta?

The Magna Carta was a charter agreed upon by King John and rebel barons in 1215. It aimed to limit royal power and protect certain rights, establishing the idea that even the king was subject to the law.

Why did the barons rebel against King John?

The barons were frustrated by John’s heavy taxes, military failures in France, arbitrary justice, and authoritarian rule. Their discontent pushed them to demand written guarantees limiting the king’s authority.

Where and when was the Magna Carta signed?

The charter was sealed (not signed) by King John at Runnymede, near the River Thames, in June 1215. The meadow became symbolically linked to liberty and constitutional government.

What were the most important clauses?

Notable provisions included protection from unlawful imprisonment, access to swift justice, and limits on taxation without baronial consent. Clause 39 and 40 became especially influential in later legal traditions.

Did the Magna Carta succeed immediately?

No—King John quickly sought annulment from Pope Innocent III, triggering renewed civil war. Only later reissued versions under subsequent kings gained lasting authority and respect.

Why is the Magna Carta important today?

The document inspired concepts such as due process, the rule of law, and constitutional limits on government power. Its legacy influenced the English Bill of Rights, the U.S. Constitution, and global human rights ideals.

📜 Test Your Knowledge: Magna Carta Quiz

📜 Glossary of Magna Carta & Medieval Legal Terms

Magna Carta

The “Great Charter” sealed in 1215 at Runnymede, establishing that the king was subject to the law.

Runnymede

The riverside meadow where King John met the barons and agreed to the Magna Carta.

King John

The English king whose dispute with his barons led to the Magna Carta’s creation.

Feudal Barons

Powerful lords who rebelled against King John’s rule and demanded legal protections.

Rule of Law

The principle that everyone—including the monarch—is bound by the law.

Due Process

A legal guarantee that no one can be deprived of rights without fair procedures, rooted in Magna Carta clauses.

Habeas Corpus

A later legal concept inspired by Magna Carta, protecting individuals from unlawful imprisonment.

Charter of Liberties

An earlier 1100 royal document that influenced Magna Carta’s ideas about limiting kingly power.

Common Law

England’s developing legal system, shaped by customs and judicial decisions rather than royal decree alone.

Council of Barons

A group appointed by the Magna Carta to ensure the king followed its terms, an early check on royal power.

📚 References & Further Reading

📜 The Magna Carta (1215) Historical Images